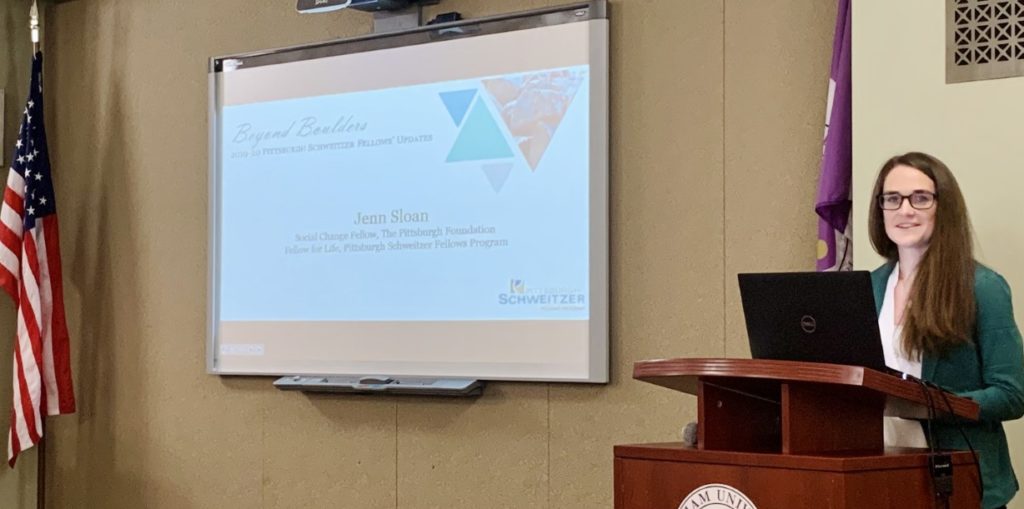

Fellow for Life, Jenn Sloan, was the featured speaker at our Beyond Boulders: Fellows’ Update on Sunday, January 12th. Jenn is currently the Social Change Fellow at The Pittsburgh Foundation.

Below is a full transcript of her inspiring and resonating speecjh.

I was a Schweitzer Fellow during my Master’s Program in Public Health at Pitt. My site was the Birmingham Free Clinic, where I had served as an AmeriCorps service member before starting my graduate studies. My vision, which started brewing toward the end of my AmeriCorps year, was to address the social determinants of health that were impacting our patients.

I was blown away each day at clinic. The clinic staff and volunteers brought so much care and thoughtfulness and necessary creativity to their medical decision-making and to each patient encounter. I fell in love quickly with Birmingham’s mission, its culture of going above and beyond for patients, and the generous energy that buzzed about the clinic each day.

But I also knew we could do more.

We could — and we did — diagnose a patient with asthma and provide the necessary inhalers to treat that asthma, for as long as they needed inhalers from us. But what about the root cause. What triggered the asthma? Could we do anything about that? Could we help them acquire a vacuum for their dust triggers? Or could we support them in approaching their landlord about eliminating the cockroaches or mice in their home?

What about a patient that was given prescription medications that had to be taken with food? Did the patients have enough food, each and every day of the month? If not, could we give them tools to become more food secure? Could we help them apply for a job, or apply for SNAP benefits, or locate a food pantry near their work or home?

I came to believe that this comprehensive care was central to the mission of the clinic, and I set out to create a service to provide that care. I got a green light from the clinical director at Birmingham, but she also encouraged me to apply for the Schweitzer Fellowship to help carry out the project.

As a many-time Schweitzer mentor, and still today, Mary Herbert convinced me that the professional development, peer support, and project structure that being part of the Fellowship afforded could only augment the quality of the program I had in mind. And as always, she was right. Without a doubt, Schweitzer helped me to do just that.

It started with the interview. For me, that interview set the stage for the high standards of quality work, community dedication and attention to detail that is expected of all Schweitzer Fellows.

For those in the room who haven’t been through a Schweitzer interview, it’s an intense combination of group and individual interviews, as well as a group problem-solving exercise where you present your solution to a panel of interviewers who jump into character and are defensive, relentless, and aggressively combative. It was truly jarring. To me, those two hours were more intense and more stressful than my nine hour interview at RAND where I worked after my Masters.

But that high standard is absolutely what our organizations and our communities deserve. They deserve the very best from us, day in and day out. And that was one of the most important lessons I took away from Schweitzer. The high standards I had for myself in other areas of my life, like my school work, must absolutely be equal or even higher in my volunteer work. Our communities deserve that.

At Birmingham, what started as a simple but, admittedly ambitious, vision for a safety net clinic to provide patients with social determinants of health care, came to life during my Schweitzer Fellowship. I did not do this alone. I had an incredible partner in my Schweitzer mentor, who poured her time and energy and expertise and love into this project with me. Together, we found an old desk in a UPMC warehouse and set up a physical space at clinic in which this care could occur.

We spent hours scraping existing social service referral documents, grilling our friends in social work and case management, and digging into the Google Machine to create a database of existing services and programs that we could refer patients to. We developed a six-hour training for our volunteers and we crowdsourced ideas for training topics and ice breakers and formats with my fellow Fellows.

In our first semester, we recruited, interviewed and trained 10 undergraduate students to operate this “social services help desk.” Modeled after the monthly Schweitzer gatherings, we held reflective sessions every other week. We brought these volunteers together for peer learning, for problem solving of complicated patient cases, and for celebrating their hard work.

One of the most valuable lessons that I took away from my Schweitzer Fellowship was: Do the work before you lead the work.

Being at the help desk 1-2 times a week was invaluable to leading the program successfully. Yes, I was at the help desk because Schweitzer required me to be there, providing direct service. Not that I didn’t want to be there. Hands down, those were my favorite hours of the week. But it was a huge effort to stand up this program, and I felt pulled by the administrative work that was required to keep the program afloat.

I think that happens a lot. We get pulled away from the people we want to serve by the grant writing and the book keeping and the inventory recording that all happens behind the scenes. Don’t get me wrong, that work is necessary. But Schweitzer instilled in me

the importance of being part of the work on the ground, in order to do the best

work leading behind the scenes.

Though

a very different setting, I applied this learning at RAND, where I was

conducting and coordinating community engaged research. Everyone on my research

team took the surveys we had developed, just as our participants would. The

programmer, the statistician and the administrative assistants

— all

needed to feel a sliver of the experience that our participants have. I believe

it made the data cleaning, analysis, writing and publication decisions stronger

and more grounded.

Doing the direct service work, as Schweitzer requires, has also made me a better leader and a better person because of the lessons I have been taught by the patients I have worked with. One of those lessons was about making assumptions.

One of my very first patients shared excitedly that he had a job interview the next day. His resume was hand-written on a piece of scrap paper and he asked if he could use a computer. Of course. Together we found a resume template he liked, and I told him that I’d check on him in a bit.

When I went back ten minutes later to see how he was doing, the screen was still blank, and he looked sad and embarrassed. He sheepishly offered, “I don’t really know how to type.”A few hours later, he walked out of clinic, with not just a resume typed and printed on nice paper and slid into a brand new folder, but a typing lesson under his belt as well.

His was a happy ending. He typed his own resume and he got the job. But at a cost. Without realizing I was making an assumption, I assumed he could type and navigate Microsoft word. And in making that assumption, I left him to fend for himself. I damaged, temporarily, the joy and pride that he walked into clinic sharing with us.

Assumption-making can be REALLY harmful. Being aware of, and not acting on my own assumptions is something I am still actively working on. I encourage you to join me in that work.

Another patient who I think about all of the time, was a brilliant, street homeless man who urgently needed housing, and just as urgently wanted to be able to bring his dog with him. Housing provider after housing provider that I called told me I was nuts, of course they don’t allow dogs.

As a dog lover myself, even I started wondering whether housing without his dog might be better than being homeless with his dog. But the patient was adamant. His dog was his emotional support and his purpose. And you know what? He was absolutely right. He was the expert in his own life, his own needs, his own community. So are all of the people that we serve.

Schweitzer instilled in me the importance of placing our patients’ expertise and hard work at the center of the conversation, allowing our patients to be the teachers, and us the students. Giving them the voice and tools and open-mindedness to tell you about themselves, their lives, and their communities is so important. This notion applies beyond just individual encounters.

Incorporating the expertise of your community into your data collection, decision-making, and knowledge sharing is vital. Listen to and share your platform with the true experts. In the organization I work for now, The Pittsburgh Foundation, voice is a core value. It’s one we try to center in each activity.

In our research and data collection, we go out to the users, clients, patients, providers, and policy makers, and interview them. We use this information to shape our grant-making and our policy and advocacy work, so that it reflects the barriers and hopes of the community, that are shared directly with us, in their own words. They are the experts in their own field, after all.

So I would encourage you to think more intentionally about how to incorporate the voice of your community into your planning, programming, evaluation and reporting processes.

- Is your communities’ voice represented in your monthly reports?

- Is it represented in your presentations today and in your posters?

- Are you sharing your platform with your community to help their voice be heard?

I still can’t really believe that I get to say this, but nearly seven years later, my Schweitzer project is still going strong. The program has a new name, and a real logo. Connections4Health has a new administrative home and a paid, full-time program director. It’s operating in three additional sites in Pittsburgh and is currently exploring expansion to a rural site. It looks different now, for sure.

In our first year, our referrals database was an excel spreadsheet, and our patient records were word docs, one for each patient. Fast forward to today, and we are on our fourth iterations of these program essentials. Now we have a searchable database and patient portal that are linked to each other within a secure, web based software. The difference is amazing.

Our training has evolved in countless ways based on feedback from our volunteers. Even our program evaluation data collection looks different and much improved. It’s even integrated into the daily workflow with minimal burden and focused outcomes.

I’m really proud of what the Connections4Health team has accomplished. But I’m not here to advocate for you to do what I did. That’s not realistic, and every project, every site and every community is different. And so are each of you. But I am here to urge you to leverage all that Schweitzer is and can be to do the very best work on behalf of and alongside of your community, whatever that looks like.

Schweitzer provides important and necessary structure and accountability and peer support but the boundaries are loose. Push the boundaries of what you can give your projects, and what your projects can give to your communities. As you think about your boundaries, please think seriously, deeply, and genuinely about what happens after your fellowship ends. What does your site look like without you? What about the people you have served?

Entering into a community, establishing trust, supporting the mission and leaving one year later CAN cause harm. There are people and organizations that are skeptical of programs like the Schweitzer program, where the benefit could flow more to the Fellow than to the community they claim to serve. That flying in and flying out is a luxurious service learning that often leaves communities and organizations hurt and harmed. Please do not forget that.

As you look forward into the second half of your fellowship year, I urge you to put real, genuine and active structures, policies, and organizational capacities in place to ensure that not only do you do no harm, but you advance and empower your community to continue on.

I’ll leave you with one more piece of advice. And I may get in trouble for this one…collectively, our end goal should be to put Schweitzer out of business.

I’ll give that some context: If our health care system was inclusive and didn’t have gaps in care or coverage for our most vulnerable, a safety net clinic like Birmingham wouldn’t have to exist. If everyone had access to safe and affordable housing, we wouldn’t need homeless shelters or services. The penultimate goal we must strive for, as a service field, is to not have to exist at all.

So, while you are supporting the individuals and organizations you serve in really important ways, I urge you to pick your head up, and look at the larger picture. Consider the policies and systems and ideas that enabled the situation that you find your communities in:

- The zoning policies that facilitated the segregation of Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods

- The policies that dubbed those with disabilities less than human, OR

- The lack of environmental laws that are giving way to high rates of asthma in our city’s youth.

If we only support the individuals, and don’t change the policies, we will never put ourselves out of work.

In the book titled “How to be an anti-racist,” the author, Doctor Ibram Kendi writes, “Americans have long been trained to see the deficiencies of people rather than policy. It’s a pretty easy mistake to make: People are in our faces. Policies are distant. We are particularly poor at seeing the policies lurking behind the struggles of people.”

We must do better. Of course, we should care for those who are suffering in front of us. But, simultaneously, we must use our platforms to dismantle the policies and ideas that enable this suffering.

Together, let’s strive for a city in which the Birminghams and Schweitzers are no longer needed.

Graduate studies are hard. The work of the Schweitzer Fellowship is hard. You all are out there, doing both. Thank you for committing yourselves to learning from, and serving alongside of, others. I am so grateful for you, and I applaud each of you.

As is only fitting, I will leave you with the words of Doctor Albert Schweitzer, “Do something wonderful, for someone may imitate it.”